Investing in Europe in 2020 – The Year Ahead

An overview of some European key themes and political risks for 2020

2020 brings with it the 10th year of recovery since the global financial crisis. Equity markets continue to break records, ample credit is available, yet the bullish performance appears cosmetic at times and investing in Europe in 2020 is fraught with political risks. The US deficit doubled from $385bn to $779bn last year, the UK scrapped its 47-year old partnership with the EU and the global economy, awash with approximately $16 trillion of negative-yielding debt, is starting to sputter. Ongoing political turmoil, not just from extreme right-wing parties in places such as Germany, France, and Italy, but also from the extreme left in Spain and more recently Ireland, complicate investment decisions even further as we enter the new decade.

Tariffs have been one of the reasons behind the global slowdown. The “tit-for-tat” fines have disrupted more than $500bn in trade; to date, the US has placed tariffs on over $400bn worth of goods while US allies and enemies have retaliated with nearly $100bn in new levies. America’s latest tariff on EU goods is a response to a recent WTO ruling on Airbus subsidies from the EU. The WTO granted the US the right to recoup up to $7.5bn annually for the subsidies. Brussels has lodged its own $12bn counter-complaint with the EU for US subsidies to Boeing but is still awaiting a decision.

In the meantime, several European countries have retaliated with a series of digital tax proposals largely aimed at US technology enterprises. France nearly moved ahead in implementing its 3% digital tax but rolled back legislation after the US threatened to double the price on $2.4bn worth of French goods. The UK also tabled its digital tax that was due to come into force this April 2020. The EU may soon also subject the US to new carbon taxes as the European Commission drives its green agenda forward.

The turmoil and skirmishes have had an impact. Eurozone GDP grew by 0.1% last quarter, its weakest result since 2013 while European equities were hit with $100bn in outflows last year. And even though Q3 YoY sales and profitability were healthy across most sectors in the Stoxx Euro 600 and nearly 60% of the companies posted a positive earnings surprise, European companies trade at a heavy discount to US corporates in both the public and private spheres. Forward P/B ratio of Stoxx Europe 600/S&P 500 is at record-breaking lows despite the European benchmark’s strong performance over the past several years.

European public market valuations reach new highs

Yet European Forward P/B vs. S&P 500 Forward P/B ratio at record lows

Source: Bloomberg

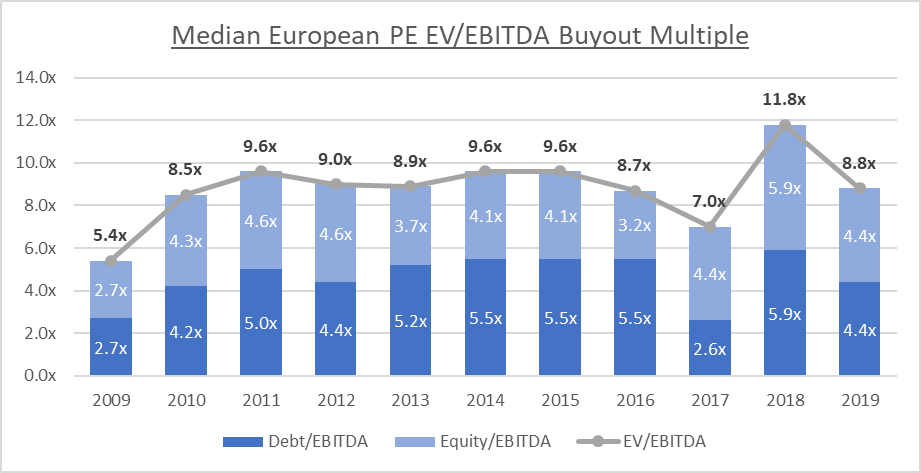

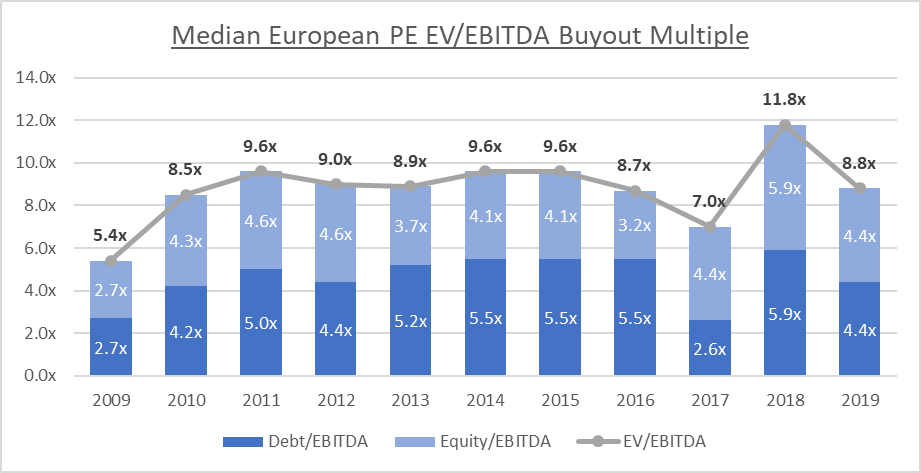

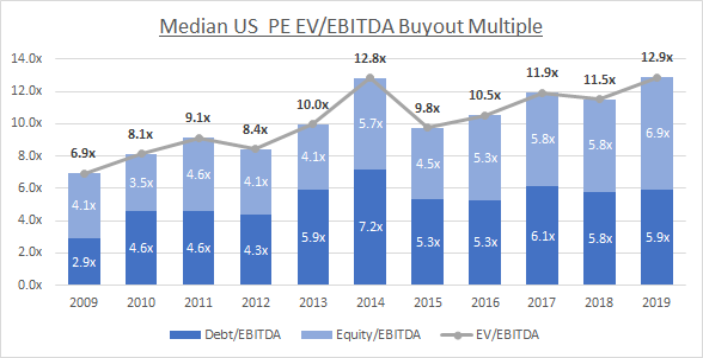

In the private markets, the median US LBO acquisition multiple hovers around 12.9x EBITDA. Across the Atlantic, the median European buy-out multiple has mostly trailed those of US buyouts since 2013. The current 8.9x EBITDA, European median buyout multiple now sits nearly 4 turns below the US median, representing the largest divergence from the US since the crisis. Trade skirmishes aside, one might ask if Europe unfairly undervalued? What’s going on and is this an opportunity? We look at some of the key developments and risks in the main markets investors should be considering in the coming year.

EU

“Without the free movement of people, there can be no free movement of capital, goods, and services. Without a level playing field on environment, labor, taxation and state aid, there cannot be the highest quality access to the single market. Without being a member, you cannot retain the benefits of membership” – Ursula von der Leyen, Charles Michel and David Sassoli joint statement – 31 January 2020

Last year signaled leadership change at Europe’s main institutions with important ramifications on how the continent moves forward in 2020, post-Brexit and beyond. The new leaders have made an overwhelming push to bring environmental issues to the forefront of its policies and cement Europe’s role as the climate change leader. Below are some of the names leading the charge in 2020.

European Council

Former Belgian Prime Minister Charles Michel took over as President of the European Council in December. He will lead the 27 EU council member states for the next 2 ½ years in implementing the EC’s Strategic Agenda set last June. Under Michel’s leadership, the EC will focus primarily on protecting its citizens, developing Europe’s economic base, climate change and promoting European interests globally. Immediately following his start, Michel pushed member states to ratify the 2050 net-zero greenhouse gas emissions target.

European Commission

Ursula von der Leyen, previously Germany’s defense minister, officially took over as President of the European Commission in December and has wasted no time in laying out the EC’s agenda. In a speech to Parliament last summer, President von der Leyen pledged a Green Deal for Europe within her first 100 days of office. President von der Leyen has not only expressed her desire to halve Europe’s CO2 emissions by 2030 but also to transform the region into the first climate-neutral continent by 2050.

The EC’s race to carbon-neutrality includes partitioning a section of the European Investment Bank to focus on climate-change initiatives and arming it with €1 trillion over the next decade to finance green projects. The EC estimates that €290bn / year in infrastructure and energy investments will be needed after 2030 to meet these enhanced requirements.

In addition to the environment, the Commission will spend the next 5 years focused on five other key priorities. Broadly, they encompass: 1) Completing the capital markets union, 2) Protecting the European way of life (e.g. anti-terrorism, tighter immigration laws, anti-discrimination, gender equality, etc.), 3) Promoting a stronger Europe in the world, 4) Pushing for European democracy, and 5) Promoting a Europe fit for the digital age.

Key people pushing these initiatives in the new commission include Frans Timmermans from the Netherlands, who is charged with leading the Green Deal, Valdis Dombrovskis from Latvia and Margrethe Vestager from Denmark. Vestager is well known for her pursuit of US technology giants in her role as European Commissioner for Competition.

European Parliament

David Sassoli was elected as President of the European Parliament last July. He leads a reduced 705 electorate from 27 countries post-Brexit. Sassoli has also turned his attention to climate initiatives, declaring an immediate climate emergency and calling on all members to reduce global emissions from shipping and aviation sectors echoing the Council’s 2050 EC target.

European Central Bank

Ex-IMF head Christine Lagarde took over from Mario Draghi as head of the ECB last November. Before leaving, Draghi lowered the ECB’s main deposit facility from -0.40% to -0.50% and reinitiated bond purchase programs to the tune of €20bn/month after having called off QE in Feb 2019. As a final parting gift, Draghi launched the ECB’s third round of TLTRO in September, raising the gross amount outstanding in the program to €650bn.

Many argue that Draghi’s monetary policies helped maintain Eurozone stability throughout the various crises and kept deflationary pressures at bay. Detractors argue that growth in the Eurozone is anemic and that insufficient regional inflation proves Draghi’s monetary policy have failed. European banks have been particularly critical of Draghi’s policies. The negative deposit rate means that these banks are charged a fee on the €1.8 trillion parked at the ECB.

Resistance to Draghi’s policies has not come exclusively from voices outside the ECB. Members of the ECB governing council argue that the threat of regional deflation which existed back in 2014 never materialized and that loose monetary experiments should now be scrapped. When QE was reinitiated, Sabine Lautenschläger, governing council member from Germany, resigned.

Lagarde will need to find some balance within the bank this year. She has launched a comprehensive review of the ECB’s monetary policy targeting a 2020 year-end completion. In her inaugural speech, Lagarde urged local governments not to rely solely on ECB monetary policy for growth, but to boost spending and to ‘[take] advantage of domestic markets’. Hinting at what may come once the review is complete, Lagarde’s staff offered some guidance in December on their thinking in a post-Draghi era. Importantly, it advocated the continued use of Draghi-era tools (negative interest rates, asset purchases, etc.) but argued for increasing the interest rate target from “close to 2%” to “2%”.

ECB forecasts the euro area to grow at 1.1% in 2019 and 1.2% in 2020. The concerted drive to carbon-neutrality will impact many of Europe’s heavy industry companies as the cost to implement these targets is substantial. Cost estimates to achieve EU carbon neutrality are ~$2.5 trillion over the next ten years. This becomes more problematic considering Brexit has left a shortfall of ~ €12bn / year in the EU budget.

France

“Notre Dame cathedral is still in a state of peril.” – General Jean-Louis Georgelin – Heading the Restoration of Notre Dame

| Stats | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

| YoY Real GDP Growth (%) | 1.7% | 1.4% | 1.3% |

| YoY CPI Inflation (%) | 1.8% | 1.2% | 1.2% |

| Debt (% of GDP) | 98.4% | 98.8% | 98.7% |

| Budget Surplus (Deficit) (% of GDP) | (2.5%) | (3.1%) | (2.2%) |

Source: France Draft Budgetary Plan 2020

Political Parties: Left: La France Insoumise (Jean-Luc Mélenchon), Center-Left: Parti Socialiste (Olivier Faure), Center: La République en Marche or “LREM” (Emmanuel Macron – President), Center-Right: Les Républicans (Damien Abad), Far Right: National Rally or “RN” (f.k.a. National Front) (Marine le Pen).

Macron’s Initial Problems

Macron faces a challenging year ahead in 2020. Last year’s partial incineration of Notre Dame, the famous cathedral in the center of Paris, is perhaps emblematic of Macron’s tenure to date. Macron won France’s 2017 national elections in part by promising to overhaul the country’s tax system, update its labor market, healthcare system, and eradicate government bureaucracy. Since his election, however, many of his proposals have stalled after facing heavy backlash from the public, media, critics and more specifically from protestors in the “yellow vest” movement.

At its height in November 2018, the yellow vest movement overtook the streets of France with as many as 282,000 anti-Macron protestors. To repair the damage with the French population, Macron rolled back several of his proposals, managing to momentarily quiet French ire. By the time the April 2019 cathedral fire occurred, the number of anti-Macron protestors taking to the streets had fallen to a less alarming 23,000. Macron interpreted the decreased protestor numbers as an indication to relaunch his reforms initiatives.

New Initiatives

France announced a new set of initiatives in its 2020 budget, pledging to cut taxes by more than €10bn in the hopes that private consumption and corporate investment would drive growth by as much as 1.3%. The European Commission warned France that its budget risks breaking the EU Stability and Growth Pact as government debt as a percent of GDP is now expected to increase from 98.7% in 2020 to 99.2% in 2021 causing worry in Brussels.

Prime Minister Philippe summarized the newest set of reforms last summer, which, aside from tax cuts for the middle class, include a reduction in unemployment benefits for high earners. However, it was Macron’s insistence on increasing the retirement age from 62 to 64 and capping pension benefits that reignited public opprobrium.

France holds municipal elections in March 2020. The elections will be the first local vote of importance since yellow vest demonstrations restarted. Far-right leader Marine le Pen has used the surge in protests to highlight her party’s support for a strong welfare state, countering Macron’s pension reforms and winning points with the French population. A National Rally success in local elections this March could become the platform that delivers Marine le Pen the French presidency in 2022. Despite these challenges, French public markets have enjoyed a renaissance of sorts; the CAC 40 is up over 20% over the last 12 months and is at a decade high. Expect some softening in the run-up to March elections and a correction if le Pen’s Rally party advances its position post-election.

Germany

“With the aim of making the CDU stronger, I have today, after extended reflection, informed the party board and leadership team [that] I will not seek to become a candidate for the office of German Chancellor,” – Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer –Leader of the Christian Democratic Union’s – 10 Feb 2020.

| Stats | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

| YoY Real GDP Growth (%) | 1.5% | 0.5% | 0.5% |

| YoY CPI Inflation (%) | 1.5% | 1.4% | 1.7% |

| Debt (% of GDP) | 61.9% | 59.8% | 57.8% |

| Budget Surplus (Deficit) (% of GDP) | 1.9% | 1.3% | 0.8% |

Source: Germany Draft Budgetary Plan 2020

Political Parties: Left: Left Party (Katja Kipping), Center-Left: Social Democratic Party or “SPD” (Saskia Esken, Norbert Walter-Borjans), Center-Right: Christian Democratic Party or “CDU” (Angela Merkel – Federal Chancellor until 2021. Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer CDU leader until Summer 2020), Christian Social Union (Markus Söder) or “CSU”, Free Democratic Party or “FDP” (Christian Linder), Far Right: Alternative für Deutschland or “AfD” (Jörg Meuthen / Alexander Gauland).

Challenges facing the Grand Coalition

In 2018, Merkel announced her 2021 resignation plans with the hope that a transition to her designated successor, Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer (“AKK”), would progress smoothly. To date, it has been anything but. Germany’s lagging economic performance and political turmoil render the country’s near-term prospects dim. The Bundesbank cut 2019 growth expectations from 1.5.% to 1.0% in its 2020 budget reflecting its own worries about the global economic slowdown and a weakening local economy. Budget plans target an even more pessimistic GDP growth at 0.5% and 1.5% for 2019 and 2020 respectively leaving many asking the question ‘what happened to Europe’s economic engine?’

Dogged by gaffes and missteps, AKK’s leadership of the Christian Democrats is coming to an end after she announced her resignation this February. Coordinated voting between the CDU and Far-right AfD officials in Thuringia’s February regional elections proved to be too much for the CDU party prompting AKK’s exit. Kramp-Karrenbauer also announced that she would not be running for German Chancellorship when Merkel steps down.

The CDU is not the only party facing problems within the Grand Coalition. The SPD suffered historic losses in last summer’s European elections and the collateral damage was significant. Ex-SPD leader Andrea Nahles resigned after winning a paltry 15.5% of the vote (a decline of 11%), ushering in the party’s current leaders Norbert Walter-Borjans and Saskia Esken. Both were relatively unknown but had expressed their desire to end the alliance with Merkel’s CDU. After their election, the pair had pivoted away from promoting the breaking up the coalition to focus on fiscal expansion.

Currently, there are signs of renewed strain in the coalition as Esken came out publicly against the CDU after the Thuringia incident. Now that AKK has stepped down, the race for CDU leadership is open. CDU heavyweight and vocal critic of Angela Merkel, Friedrich Merz is pushing to take over the party and take it further to the right.

Germany’s External Pressures

Ongoing tariffs and trade discussions place additional pressures on the German economy. Germany’s automotive trade body VDA announced that 2019 YoY car production and exports fell 9% and 13% respectively leaving German auto production at a 23 year low. Not only have US-EU tariffs disrupted German auto sales, but US-China trade disagreements have also hit German auto manufacturers. The major German auto producers control 4 large factories in the US employing over 118,000 people. Of the 750,000 German vehicles that were produced at US plants in 2018, almost 60% were exported to China. VDA estimates that US tariffs could damage the German auto sector by as much as of €19bn.

As exports decline, Germany will look internally for growth. The ECB had already been nudging Germany to use its budget surplus to support fiscal expansion at home, specifically recommending clean energy infrastructure and education as target sectors. Lagarde’s call for countries to do more locally suggests the ECB will maintain its previous stance towards German fiscal expansion going forward. Thus far, Germany announced a “distinctly expansionary” 2020 budget in response. It includes the “Digital Pact” which directs ~€5bn of federal funds into the German schools. And crucially, in line with the country’s current push towards carbon neutrality, Germany plans to spend approximately €9bn in 2020 and €55bn by 2023 implementing measures under its Climate Action Program.

Equity markets remain ambivalent to German recessionary pressures for now. The DAX is up nearly 25% over the year, despite 70% of the index’s revenues coming from exports. Credit markets have been equally bullish though the failure of Germany’s to place all its €2bn zero-coupon -0.11% yield paper last summer suggests that sentiment may be shifting. Climate change may be the place where Germany regains its footing. RWE AG, Germany’s largest polluter, announced its own carbon-neutral 2050 target. As the EU pushes forward with its Green initiatives and legislation, we will likely see more German industrials announcing carbon-neutral plans in 2020.

Greece

Learn to bear bravely the changes of fortune. – Periander 2d Tyrant of Corinth, Greece 668-584 BC

| Stats | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

| YoY Real GDP Growth (%) | 1.9% | 2.0% | 2.8% |

| YoY CPI Inflation (%) | 0.8% | 0.6% | 0.7% |

| Debt (% of GDP) | 181.1% | 173.3% | 167.8% |

| Budget Surplus (Deficit) (% of GDP) | 1.1% | 1.4% | 1.0% |

Source: Greece Draft Budgetary Plan 2020

Political Parties: Far-Left: Syriza (Alexis Tsipras), Center-Left: PASOK (Fofi Genamata), Center-Right: New Democracy or “ND” (Kyriakos Mitsotakis – PM), Far-Right: Independent Greeks (Panos Kammenos), Neo-Nazi: Golden Dawn (Nikolaos Michaloliakos)Source: Greece Draft Budgetary Plan 2020

New Prime Minister and Reforms

We continue our bullish view on Greece and new Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis. Greece has progressed significantly since its €110bn Troika-led 2010 bailout. A decade on, there are indications that Greece is turning the corner. The country still faces significant problems heading into 2020 including high unemployment and aging infrastructure. Greece’s debt burden remains one of the highest in the EU and the nation’s main banks still suffer from elevated NPL ratios.

However, Greece seems to be addressing these challenges. Unemployment fell from ~30% in 2014 to 17% in 2019 and is forecasted to fall further to 15% in 2020. Private consumption and investment are expected to drive growth 2% in 2019 (vs. 1.9% in 2018) and 2.8% in 2020. This compares favorably to Euro area forecasted growth of 1.2% in 2020. Greece is also on target to exceed its primary surplus targets for the 5th year running – reaching 3.5% of GDP in 2019. The structural balance is forecasted to reach a surplus of 1.9% in 2020 while debt, though still elevated at 168% of GDP, has materially decreased from its 2018 high of 181%.

Since his election, last July, Prime Minister Mitsotakis has advocated for business-friendly legislative reforms. Withholding tax on domestically listed corporate bonds and on debt issuances from local banks that need to meet MREL requirements have been scrapped for residents of several countries. Value-added taxes on new buildings construction has been suspended for 3 years to help kick start the construction industry.

Other reforms include cutting the corporate tax rate from 28% to 24% and reducing the dividend tax rate from 10% to 5%. His administration wants to close down all lignite-fired coal plants by 2028, update the insolvency regime by April 2020 and complete key asset disposals under Greece’s privatization programs (e.g. Public Power Corporation, Public Gas Corporation, the sale of 30% of Athens Airport, Egnatia Motorway Concession, and 10 regional ports).

Reopening of Financial Markets

Moreover, Greek banks continue to address legacy bad debt. For example, Alpha Bank launched the Galaxy program in December to reduce its bad debt load from 44% in 2019 to under 20% in 2020. That same month, the government approved the Hercules Asset Protection Scheme which offers Greek banks state guarantees to help securitize NPLs stranded on their balance sheets. The scheme is expected to assist in reducing bad debt circulating in the system by a further €30bn. Overall, NPLs have fallen from a high of ~50% (~€110bn) in 2016 to 43% (~€75bn) by mid-2019. The country is targeting ~20% NPL ratio (~€26bn) by the end of 2021.

The European Commission appears happy with Greece’s progress as well. The EC lifted 2015 capital controls this past September after Greek banks fully repaid the outstanding €1bn from previous emergency liquidity assistance loans. The EC also rewarded Greece with an initial €1bn distribution from a €4.8bn post-bailout pledge. Distributions are contingent upon the outcome of periodic surveillance audits, which implies Greece has passed close financial scrutiny from the EU. This initial distribution will allow Greece to reduce its €12bn in outstanding debt to the IMF. The EC issued another favorable audit in November which puts Greece on track to receive another disbursement package worth ~€760mm in semi-annual tranches up to mid-2022.

Greek equity and credit markets are taking notice. Fitch upgraded Greek debt from BB- to BB in January; other agencies will likely follow suit this year. Greece, which is targeting investment-grade status by 2021, successfully tapped debt markets several times last year and, this January managed to issue its first 15yr paper since 2009. The €2.5bn issue was well received, bringing in over €18bn in orders and pricing at a sub 1.875% yield. The benchmark ASE outperformed the S&P and all other main EU indexes with a 12-month performance of 40%. We expect to outperform again in 2020 provided Mitsotakis can continue to implement his agenda.

Ireland

“These three wise men of failed government and broken promises still believe that they’re going to have things all their own way.” – Mary Lou McDonald – Leader of Sinn Féin after Ireland’s 2020 General Election

| Stats | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

| YoY Real GDP Growth (%) | 8.2% | 6.3% | 2.9% |

| YoY CPI Inflation (%) | 0.2% | 1.0% | 1.5% |

| Debt (% of GDP) | 63.6% | 59.3% | 56.5% |

| Budget Surplus (Deficit) (% of GDP) | 1.7% | 1.6% | 0.6% |

Source: Ireland Draft Budgetary Plan 2020

Political Parties: Left: Sinn Féin (Mary Lou McDonald since Feb 2018), Greens (Eamon Ryan), Center-Left: Labour (Brendan Howlin), Center-Right: Fine Gael (Leo Varadkar – Taoiseach), Fianna Fáil (Micheál Martin).

The Rise of Sinn Féin

Leo Varadkar stepped down from his position of Taoiseach in February after Irish Parliament was unable to decide on a new premier. The Fianna Fáil / Fine Gael confidence and supply agreement, which was extended for two years at the end of 2018, became untenable after health minister Simon Harris faced the prospect of losing a no-confidence vote from the Fianna Fáil party. After his minister was forced to step aside, Varadkar faced mounting pressure from Fianna Fáil to step aside.

Varadkar hoped his call for snap elections in February would cement Fine Gael leadership. Instead, the election ultimately led to his exit as Fine Gael only won 35 (22%) seats of the 160-member parliament (Dáil Éireann). Opposition Fianna Fáil fared slightly better winning 38 (24%) of seats. Sinn Féin, the party with links to Ireland’s historic paramilitary organization IRA, stunned Ireland by breaking the 100-year FF/FG duopoly nearly doubling its parliamentary count to 37.

With the three main parties refusing to work with one another, Ireland does not currently have a governing body. Both Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil had ruled out joining any coalition party with Sinn Féin due to its past, leaving Fianna Fáil to reach out to smaller fringe parties (Greens, Labour) to try and form a government. Parliament will reconvene on 05 March to re-try and form a government.

Ireland Confronting Changing Economic Landscape

The political turbulence is bad timing given the ongoing Brexit uncertainty. Securing an EU/UK trade deal will be crucial for Ireland as the erosion of its profitable tax base and framework in the coming years will make the country more reliant on secure trade with the UK. In 2019, 9% (€13.5bn) and 20% (€18.8bn) of Ireland’s exports and imports were with Britain.

Ireland’s low corporate tax rate (12.5% since 2003) and an accommodative tax system have attracted some of the world’s largest technology companies. Corporate tax made up 12% of all 2017 tax revenue in Ireland, of which 39% came from just 10 companies. Foreign tech companies including Apple, Google, Amazon, and Facebook, paid 80% of all Irish corporate tax.

Ongoing coordination on global tax legislation has placed increasing pressure on Ireland’s ability to continue its tax regime. In 2016, European Competition Commissioner Vestegar ordered Ireland to recoup €13bn in back taxes from Apple (the case is currently under appeal in Luxembourg). The 2017 US repatriation tax holiday on foreign profits also spurred €50bn of outflows from the Irish economy. OECD tax reform led by Pascal Saint-Amans is slated to be agreed in 2020 and its push for a global minimum tax on multinationals could render Ireland’s low corporate tax regime ineffective. Ireland expects its tax revenue to start declining in 2022, initially by €500mm and then by as much as €2bn in 2025.

Despite these challenges, Ireland continues to perform and will likely outperform in 2020. Ireland’s GDP outpaced that of all other EU countries for each year between 2013 – 2018 and its GDP growth rate will likely top that of the group again when the final 2019 data is tallied. After the EU and UK approved the Withdrawal Agreement in January, Ireland revised its GDP forecasts upward from 5.5% in 2019 and 0.7% in 2020 to 6.3% and 3.9% respectively.

Last year, we suggested the national benchmark ISEQ index was oversold as it traded as much as 17% off 2018 levels. The ISEQ has since recovered, posting +20% returns over the last 12 months, and heads into 2020 as one of the best performing European benchmarks. The near-term Sinn Féin’s agenda will be focused on consolidating power and wealth redistribution which may have some important ramifications for Ireland’s companies, but it’s unlikely McDonald will completely disrupt Ireland’s economic achievements. Growth may slow down to some extent given the new political makeup, but more important to Ireland’s continued performance will be the results of EU/UK Brexit discussions in the coming month.

Italy

“Oderint dum metuant. – Let them hate me, as long as they fear me” – Roman Emperor Caligula 12 – 41 AD

| Stats | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

| YoY Real GDP Growth (%) | 0.8% | 0.1% | 0.6% |

| YoY CPI Inflation (%) | 1.2% | 0.8% | 1.0% |

| Debt (% of GDP) | 134.8% | 135.7% | 135.2% |

| Budget Surplus (Deficit) (% of GDP) | (2.2%) | (2.2%) | (2.2%) |

Source: Italy Draft Budgetary Plan 2020

Political Parties: Independent (Giuseppe Conte – PM /Head of Coalition Gov’t), Left: Five Star Movement (TBD), Center-Left: Democratic Party or “PD” (Nicola Zingaretti), Center-Right: Forza Italia (Silvio Berlusconi), Fratelli d’Italia or “FdI” (Georgia Meloni), Far-Right: The League (Matteo Salvini – ex-Deputy PM).

Coalition Struggles to Contain Far-Right

Italy started 2020 with a weakened coalition government that had agreed to cooperate with the EU and leave its more disruptive factions to the side. Ex-Deputy Prime Minister Matteo Salvini’s political miscalculation paved the way for technocrat Prime Minister Conte to form a left-leaning coalition between anti-establishment Five Star and pro-EU Democratic parties. However, Conte’s alliance of opposites resulted in coalition infighting that led to the resignation of Deputy Prime Minister Luigi di Maio in January.

As PM Conte attempts to contain further coalition damage, Salvini’s League party continues to put pressure on Italy’s uneasy moment of stability. Fresh off October electoral wins in left-leaning Umbria, Salvini’s party performed well in Italian regional elections this January, taking key seats in Calabria and shaking up the Emilia-Romagna region. His League party lost the vote in Emilia-Romagna but managed to increase its share of the vote from the 30% obtained in Emilia-Romagna’s last 2014 local election to the recent 44% tally. Recent polls suggest that the Emilia-Romagna loss has done nothing to Salvini’s national popularity nationally. A win this PD stronghold could have set Salvini on course to becoming Italy’s next Prime Minister.

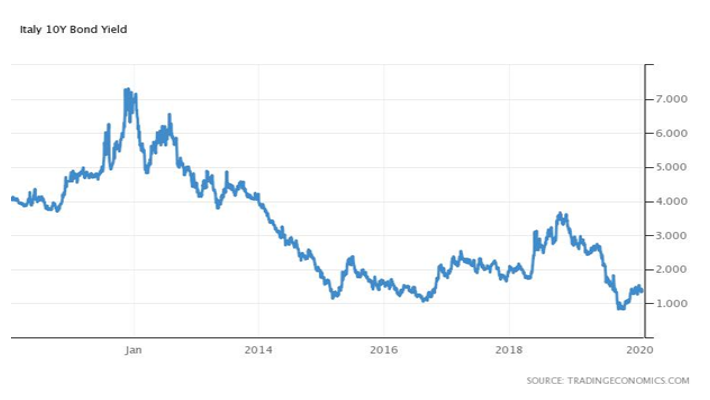

News of a Salvini comeback could not have come at a worse time for the country; despite its structural problems, Italy enjoyed a resurgence in capital markets last year. The ECB’s bond-buying announcement in September helped drive Italian 10-year yields down a further 22 bps to 0.75% while total returns on Italian sovereigns reached 8% in 2019. The Italian benchmark FTSE MIB also delivered one of its strongest yearly gains posting ~30% increase over the year.

Safe for Now

Prime Minister Conte faces several challenges in 2020. He will be watching Salvini closely while trying to steer the economy through its structural hurdles. Italy’s debt burden is forecasted to reach 135% of GDP in 2020, the second highest in the Eurozone. The fiscal deficit of 2.2% of GDP planned in the latest budget, was flagged by Brussels for potential non-compliance with the Stability and Growth Pact. And despite recent backtracking in the media, the specter of currency redenomination or of Italy leaving the EU under Salvini’s leadership remains a risk factor for anyone evaluating Italian assets.

Italy 10Y Bond Yield.

Netherlands

“In the last couple of years, this has been a government that has been spending tremendously on all sorts of (things) that the government can spend on, from defense to schools, to roads and police and of course, also on climate change” – Dutch Finance Minister Wopke Hoekstra – Davos 2020

| Stats | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

| YoY Real GDP Growth (%) | 2.6% | 2.6% | 1.5% |

| YoY CPI Inflation (%) | 1.6% | 2.6% | 1.3% |

| Debt (% of GDP) | 52.4% | 49.2% | 47.7% |

| Budget Surplus (Deficit) (% of GDP) | 1.5% | 1.3% | 0.2% |

Source: Netherlands Draft Budgetary Plan 2020

Political Parties: Left: GreenLeft (Jesse Klaver), Socialist Party or “SP” (Lilian Marijnissen), D66 (Rob Jetten, Kajsa Ollongren Deputy PM), ChristenUnie (Gert-Jan Segers, Carola Schouten Deputy PM) Center-Left: Labour Party or “PvdA” (Lodewijk Asscher) Center-Right: Christian Democratic Appeal or “CDA” (Sybrand Buma, Hugo de Jonge Deputy PM), Party for Freedom and Democracy or “VVD” (Mark Rutte – PM), Right: Party for Freedom or “PVV” (Geert Wilders), Forum for Democracy or “FvD” (Thierry Baudet).

The Netherlands has registered four consecutive years of budget surplus – a record it hasn’t achieved since the 1950s. Under Draghi, the ECB pushed member states to explore fiscal alternatives which could stimulate local growth, specifically indicating the Netherlands as a country with enough headroom to implement alternatives. In response, the usually fiscally conservative Netherlands passed a 2020 budget proposing increased local investments and lower taxes. The tax package amounts to €3bn in relief for households while the corporate tax rates fall from 19% to 16.5% for small companies and from 25% to 22% for larger companies starting in 2021.

In a setback to these initiatives, the 4-way government coalition (D66, CDA, VVD, and ChristenUnie) led by PM Rutte lost its majority in Lower Parliament (Tweede Kamer) this past October after the VVD expelled MP Wybren van Haga from its party for conflicts of interests. The expulsion left Rutte controlling exactly half of the 150 seats in the Lower house. The loss in Lower Parliament came soon after Rutte’s coalition lost its majority in the 75-seat Upper Senate (Eerste Kamer) in provincial elections last March. The coalition’s standing the Senate fell from 38 seats to 31 seats while the right-wing Eurosceptic party FvD picked up 13 seats to become the single largest group in the Dutch Senate.

The losses push Rutte to try and extend his coalition’s reach even further by teaming up with other opposition parties in 2020. Potential candidates include Greens and Labor parties. Expect both parties to leverage Rutte’s parliamentary losses to their advantage. New members in the coalition could complicate some of the fiscal initiatives put forth in the 2020 budget particularly with respect to the Finance Ministry’s proposed investment fund. The Ministry had discussed forming the investment fund in early 2020 to help boost growth, support the country’s transition away from energy, and support housing, but little information has been released since the announcement.

Spain

“We maintain our commitment to reducing the deficit and public debt levels, which will undoubtedly generate greater confidence among economic agents and enable us to have a government with greater possibilities for action and future investment.” – Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez – Davos 2020

| Stats | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

| YoY Real GDP Growth (%) | 2.4% | 2.1% | 1.8% |

| YoY CPI Inflation (%) | 1.7% | 0.9% | 1.1% |

| Debt (% of GDP) | 97.6% | 95.8% | 94.0% |

| Budget Surplus (Deficit) (% of GDP) | 0.1% | (0.3%) | (1.2%) |

Source: Spain Draft Budgetary Plan 2020

Political Parties: Left: Unidas Podemos (Pablo Iglesias), Catalan Republican Left or “ERC” (Oriol Junqueras), Center-Left: Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party or “PSOE” (Pedro Sanchez – PM), Center-Right: Ciudadanos (TBD in Mid-March), Right: People’s Party or “PP” (Pablo Casado), Extreme Right: Vox (Santiago Abascal).

Spain Puts Together a Government

This January, Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez finally won the backing of the Spanish population to form a coalition government with left-wing party Podemos after years of impasse which included two general elections in 2019 alone. Separatist parties Catalan ERC and Basque EH Bildu helped deliver the majority to Sánchez by abstaining from January’s vote. In return, PM Sánchez agreed to explore separation discussions with the groups.

The PSOE/Podemos coalition, Spain’s first coalition government in 80 years, ran on a platform of increased taxes, increased scrutiny of large financial institutions and strengthened labor and consumer rights. When the coalition was formalized, many expected the new government to enact legislation that slows down or halts Spain’s privatization plans, increases the minimum wage, and enact further rent controls.

Anti-Business or Not?

What happens going forward remains to be seen but Sánchez used the 2020 Davos forum to allay any fears investors might have voiced against Podemos’ more divisive proposals. The party, which lost 7 seats in the last election, agreed to roll back some of its demands in accepting the PSOE-Podemos coalition. The partial retreat could prove to be positive for the Spanish businesses, particularly its banking sector. Iglesias had been vocal in his disdain for Spain’s financial institutions demanding that banks repay taxpayers the €41bn used during recent bailouts. He also expressed the party’s interest in maintaining the previously nationalized bank Bankia in public hands rather than privatizing it as per EU bailout terms spooking Spain’s business community (Spain owns ~62% of Bankia after its 2012 taxpayer-funded rescue).

Last year’s uncertainty has not kept investors out of the market; Spain reached a record €8.5bn in private investments in 2019, 80% of which came from international funds. Sánchez still needs to contend with Catalonian and Basque negotiations but seems to have softened the Podemos hostilities for now. The Podemos repositioning could signal less interference from the government than previously envisaged, helping to kick-start the much talked about Spanish banking consolidation. Between 2010 and 2015, the number of Spanish savings banks fell from 45 to just over 10 main institutions and then paused. Poor margins and returns have kept merger rumors active but given the Iglesias’ prior comments, there was fear that the party would not sit idle and watch the number of financial institutions shrink further. Low valuations will continue to complicate merger discussion in the sector, but the quieting of Podemos (for now), could bring banking consolidation more into focus this year.

Switzerland

“We know that negative rates have side effects and we would like to minimize these side effects; that was the reason we changed the threshold. That gives us both the freedom to maintain the negative rates for longer, but also to cut rates if necessary.” – SNB Chairman Thomas Jordan at Davos 2020

| Stats | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

| YoY Real GDP Growth (%) | 2.5% | 1.2% | 1.7% |

| YoY CPI Inflation (%) | 0.9% | 0.8% | 0.9% |

| Debt (% of GDP) | 14.4% | 13.6% | 13.0% |

| Budget Surplus (Deficit) (% of GDP) | 0.4% | 0.2% | 0.0% |

Source: Swiss 2020 Federal Budget

Political Parties: Left: Green Party (Regula Rytz), Green Liberal Party (Jürg Grossen), Center-Left: The Socialists – SP/PS (Christian Levrat), Center-Right: Christian Democrats – CVP/PDC/PPD (Gerhard Pfister), The Liberals FDP/PRD/PLR – (Petra Gössi), Right: Swiss People’s Party – SVP/UDC(Albert Rösti).

Switzerland vs. the EU

The Swiss People’s Party (“SVP”) called a referendum to decide on Switzerland’s Freedom of Movement agreement with the EU. Immigrants make up roughly 25% of Switzerland’s 8 million people but net immigration into Switzerland was flat in 2019. The SVP wants to further limit immigration into the country, scraping agreements already in place with the EU. The vote, scheduled for 17 May 2020, would further disrupt Switzerland’s relationship with the EU. The disagreement on immigration is part of a broader discussion on the Swiss/EU trade negotiations which collapsed last summer. As a result, the EU canceled Switzerland’s equivalence standing and restricted Swiss access to the Single Market. The equivalence loss effectively banned EU equities from trading on any Swiss listed exchanges. Switzerland quickly retaliated, banning Swiss equities from trading on EU exchanges.

The disagreement is problematic considering the EU’s influence on Switzerland’s $300bn of exports. Switzerland’s top 15 trading partners make up ~80% of all the country’s trade and nearly half this is exported to EU countries. Germany alone bought 15% of Swiss exports. The Swiss government is keen to keep its relationship with the EU stable and has campaigned the population to vote against the May immigration-based referendum from right-wing SVP.

More Negative Rates

SNB Chairman Thomas Jordan is also doing his part to protect Switzerland’s exports and continues to defend his stance on negative rates. At -0.75%, the SNB and Danmarks Nationalbank, Denmark’s central bank, have the lowest interest rate of all major central banks. Chairman Jordan, who has held rates in negative territory for 5 years running, was more content when the Franc fell from near parity with the Euro to about 0.83/Euro at the beginning of 2018. However, the Franc has since rebounded to just shy of 0.95 / Euro as of this writing implying that despite the SNB’s best efforts, markets may still be gravitating to CHF as a safe-haven currency.

To temper the currency’s appreciation, Switzerland engages in Euro market interventions and has been vocal about its willingness to use future interventions as and when required. The interventions have left the SNB holding one of the largest amounts of foreign reserves, tallying ~$800bn to date, trailing only the amounts held by Japan and China. In January, the SNB added repos, a tool it had not used since 2013, to its monetary arsenal in an effort to push rates down further.

United Kingdom

“Voting Tory will cause your wife to have bigger breasts and increase your chances of owning a BMW M3” – Boris Johnson. PM of the United Kingdom during the 2005 general election.

| Stats | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

| YoY Real GDP Growth (%) | 1.4% | 1.8% | 1.8% |

| YoY CPI Inflation (%) | 1.5% | 1.5% | 2.0% |

| Debt (% of GDP) | 85.2% | 84.8% | 84.6% |

| Budget Surplus (Deficit) (% of GDP) | (0.7%) | (0.8%) | (1.1%) |

Political Parties: Left: Green (Siân Berry and Jonathan Bartley), Scottish National Party (First Minister Nicola Sturgeon), Center-Left: Labour Party (TBD as of this writing), Center- Right: Liberal Democrats (Jo Swinson as of this writing), Right: Conservative (Tory) – (Prime Minister Boris Johnson), Far Right: UKIP (TBD).

Withdrawal Agreement Complete

The landslide December election victory in which the Tory party won 364 of 650 seats in the Commons gave newly elected Prime Minister Boris Johnson the mandate to push forward with Brexit and take the UK out of the EU by Dec 31, 2020. The election led to the resignations of Labour and LibDem party leaders Jeremy Corbyn and Jo Swinson. Both parties are now working on replacing leadership. To break the previous gridlock, Johnson conceded certain points on the Northern Ireland border dispute with the EU. The current agreement sees Northern Ireland leave the EU customs union but align itself with some parts of the Single Market. In exchange, the EU dropped the contentious backstop clause within the Withdrawal Agreement.

Scotland, which voted to stay in the EU during the 2016 referendum, could become collateral damage. Scottish National Party leader, Nicola Sturgeon, wants Johnson to transfer the requisite legal rights for Scotland to legally hold another referendum on independence from the Union. Thus far, Johnson has refused the request, claiming that the issue had already been voted down in Scotland’s 2014 referendum.

Brexit Negotiations Start

PM Johnson now turns his attention to the UK’s relationship with the world post-Brexit. He has promised to deliver a trade deal with the EU by the end of 2020. The Withdrawal Agreement, which the UK and EU agreed in October serves as an intermediate bilateral framework before the UK’s final exit on Dec. 31, 2020. By this deadline, the UK and EU will need to have signed a definitive trade agreement or opt for a hard Brexit. In parallel, the UK will be crafting its post-Brexit relationship with the US.

The UK hopes to come out of Brexit negotiations with both access to the Single Market and the ability to set its own rules and regulations. However, this violates the fundamental tenets of the EU’s Single Market and is, therefore, a non-starter for EU negotiators. The UK has suggested mutual recognition as possible EU/UK trade alternative, but previous comments from EC Brexit negotiator Barnier suggest this post-Brexit framework is also unlikely. Therefore, equivalence, the EU provision that provides limited access for specific goods or services, will be a focal point over the coming year of negotiations.

Equivalence is not an ideal form of access to the Single Market as the EU can unilaterally retract the grant; last year alone it scrapped certain access rights for Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Singapore, and Switzerland. Access uncertainty would be particularly problematic for the UK’s financial sector as London’s financial service firms earn ~£200bn annually making up half of London’s entire output. In 2018, financial services alone were responsible for close to 7% of national GDP registering £60bn-£70bn in tax income for the Treasury. The EU will decide by the summer of 2020 whether the UK’s financial markets are up to its standards and therefore suitable for EU-based clients. A cursory glance at the number of issues that need to be agreed suggests the final UK exit will be delayed beyond the 2020 deadline.

UK Economic Prospects

Internally, the economy is still showing signs of weakness. GDP growth was flat YoY in 2019, partly due to Brexit related uncertainty but also because of a slowdown in UK manufacturing. Moody’s cut UK sovereign debt and banking outlooks to negative in Q4 of 2019. Before the resignation of Finance Minister Sajid Javid in February, the Tory party had discussed some of its plans to address the UK post-Brexit economy announcing prioritized sectors and proposal which included:

Health Care: Additional £34bn per year on the UK health care system NHS by 2024, including the upgrade of 20 hospitals;

Infrastructure: £100bn on infrastructure including Air traffic management, airline insolvency, and fiber roll-out. £25bn will be allocated to the strategic road network over the next five years while £5bn is committed to improving fast broadband access;

Security: £750mm allocated to the Home Office in an effort to hire an extra 20,000 people into the police force;

Business: Small retail receives a 50% discount on business. £240MM to help the high street;

Climate Change: £432mm to tackle climate change 2050 net-zero target;

Defense: £2.2bn allocation

It is unclear how these priorities will change under the new Finance Minister Rishi Sunak.

Outgoing Bank of England chief Carney moved quickly after the 2016 Brexit referendum to reduce the BoE base rate by 25bps to 0.25%. Since then, the BoE has slowly increased its base rate reaching 0.75% by late 2018, where it has since remained since. Carney intimated this January that the BoE could explore further cuts to stem persistent weakness in the UK economy, but rates have held firm thus far. Former FCA head Andrew Bailey takes over from Carney when he steps down in March 2020, but he has kept quiet regarding his views on the UK economy.

The uncertainty has not put off some of the larger institutional investors; Yngve Slyngstad of Norges Bank Investment Management ($1 trillion AUM) and Jonathan Gray of Blackstone have recently extolled the buying opportunities Brexit has produced. As more certainty comes out of the Brexit process, investment should normalize helping to drive growth again.

Undervalued European Financials

“On balance, the global industry approaches the end of the cycle in less than ideal health with nearly 60% of banks printing returns below the cost of equity. A prolonged economic slowdown with low or even negative interest rates could wreak further havoc.” – McKinsey Global Banking Review 2019

Uphill Battle for European Banks

Political turmoil and tepid economies have been principal reasons for central banks across Europe to keep interest rates at historic lows. As of this writing, major central banks’ key rates are: US Fed: +1.75%, Norges Bank: +1.5%, Bank of England: +0.75%, Sveriges Riksbank: 0%, Bank of Japan: -0.1%, ECB: Deposit rate -0.5%, Swiss National Bank and Danmark Nationalbank: -0.75%. Interest rates in Europe have been so low that a record number of US corporates crossed the Atlantic in 2019 to tap European capital markets, issuing nearly $130bn in euro-denominated debt, more than 2x 2018’s tally. This includes Berkshire Hathaway which issued its first-ever sterling-denominated bond for £1.75bn last June.

European banks are struggling with profitability, reportedly losing €8bn per year in the low rate environment. Danish banks have been reduced to offering zero and even negative interest rate mortgages to clients. In addition to low rates, Europe’s financial institutions face an increasingly more complex regulatory regime. For example, ringfencing legislation came into force in the UK last year. The law forces large banks (e.g. Barclays, HSBC, RBS and Lloyds, and Santander UK) to separate retail operations from investment banking. Estimates of total implementation cost to the industry hover around £4bn. In comparison, the issuance of new financial regulation in the US has dropped to a 40-year low as the current US administration looks to adopt a more flexible and deregulated banking framework. The US Crapo Bill, which rolled back key portions of Dodd-Frank legislation, is indicative of the regulatory “about-face” the US has taken under President Trump.

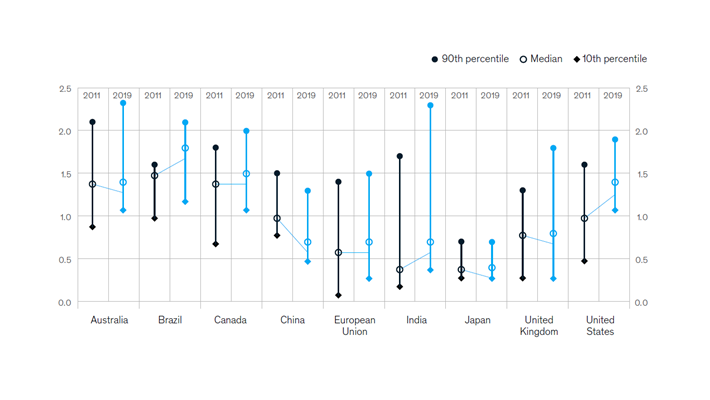

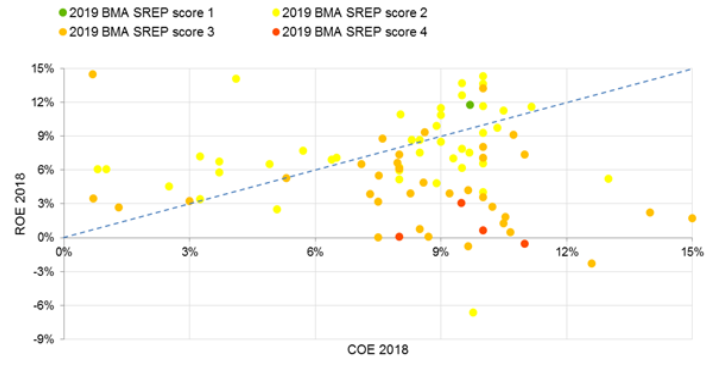

To be sure, the sector has struggled globally since the crisis; currently, 60% of banks globally do not earn their cost of capital. However, there is some truth in the complaints European banks have directed at the ECB. Europe’s banks trail their North American counterparts in profitability, averaging a 6.5% return on tangible equity (“ROTE”). US banks return more than 2x this amount, averaging a ROTE of 16%. Europe’s banks also face advanced open banking regimes which regulators have pushed to increase the market competition. These factors, plus the elevated non-performing loans, are some of the reasons contributing to the underperformance of the sector.

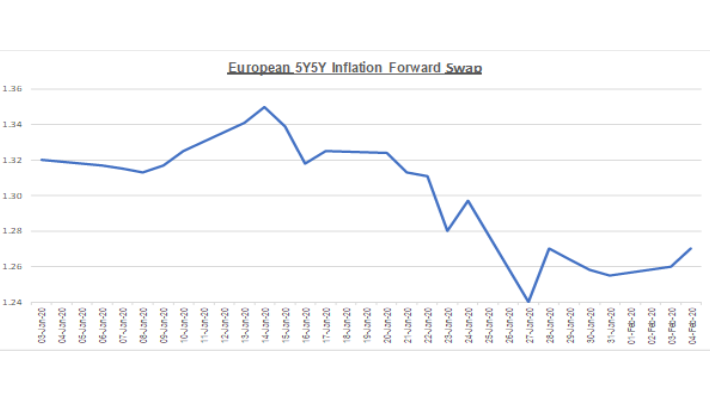

Many European banks currently trade below book value. The Euro Stoxx 600 Banking index has spent most of the past 13 years in a post-crisis sub-200 rut; the index has not been this low for this long since the early 90’s. Prospects of a near-term rate hike seem low as both economic growth and inflation remain stagnant across the region; the 5y5y inflation forward is hovering around 1.27%, not far off from the December 2019 and June 2016 lows.

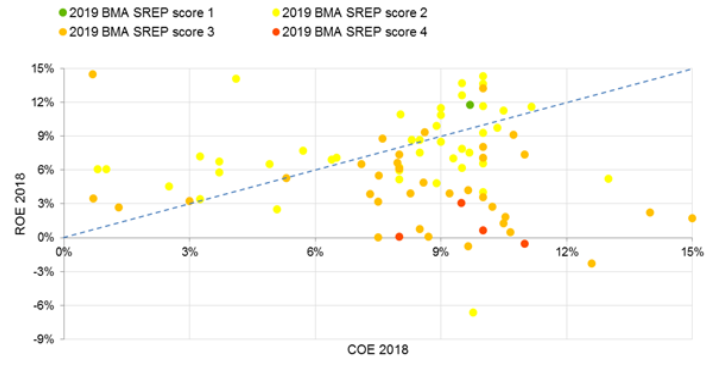

Bank 2018 Return on Equity vs. 2018 Cost of Equity

Percentile Ranking of Global Banks. 2011 – 2019

Source: McKinsey

European 5Y5Y Inflation Forward Swap

Banking Green Shoots?

But there are hints of green shoots in the sector; the EBA reported that NPLs across Europe halved from €1.15 trillion in June 2015 (6% of outstanding loans) to €630bn in June 2019 (~3% of outstanding loans). Arguably, the improving bad debt profiles of Europe’s banks have not yet been fully reflected in current valuations. Switzerland aside, central banks are starting to question negative rates. Sweden scrapped its negative interest rate regime in December labeling it counterproductive and raised its repo rate from -0.25% to 0%. There are indications that Denmark is ready to give up the experiment as well.

There is some discussion of inflation starting to return to Europe. ECB central economist Philip Lane currently sees wage pressure building in service sectors and is confident the upward pressure will trickle over into goods finally pushing inflation upwards. In addition, Lagarde’s current ECB monetary policy review suggests an understanding that the status quo needs adjustment. Talks of new tools and monetary approaches could have upside implications for ECB rates in the medium term. The proposal to include owner-occupied housing costs into the ECB’s inflation calculation, for example, could lead to upward inflation pressure. (NB: Housing prices across European markets have exploded in recent years and the lack of affordable housing has pushed up rental pricing).

Persistently poor margins and low valuations continue to fuel M&A speculation; SocGen, ING, UniCredit, Commerzbank, UBS, Credit Suisse, and DB regularly come up as cross-border merger partners, but no concrete action has taken place to date. However, Olaf Scholz’s November surprise announcement supporting a common deposit scheme may prove the be the catalyst the sector needs for cross-border mergers. The implementation of a common deposit scheme has been a key issue preventing full cross border banking integration to proceed and Scholz, Germany’s finance minister, was one of its most vociferous opponents. Finally, the ECB is quietly softening its stance against banking mergers. If one believes that “lower for longer” will either need to come to an end in the medium term or that the low rates and a shifting perception on tie-ups will lead to national and/or cross-border mergers in the medium-term, then one might make the conclusion that European banking stocks are cheap today.

Conclusion

- Without an agreement in place, bilateral trade between the EU and the US will remain subdued in 2020. The Phase 1 agreement offers initial signs of hope for European companies with US-based manufacturing subsidiaries exporting to China. However, direct tariffs remain and are likely to increase as the EU ramps up carbon and digital taxes. US trade representative Lighthizer hinted in December that the US was ready to escalate. The recent COVID-19 outbreak will weigh heavily against potential upside from trade deals. EU companies reliant on exports to non-EU countries (e.g. materials and industrial sectors) will see the bottom line impacted. Durable goods and non-durables will continue to struggle.

- The ECB continues to urge European economies towards fiscal stimulus where possible in 2020. France, Germany, Greece, and the Netherlands have announced various measures to boost private consumption and investment. Local infrastructure, healthcare, insurance, and other local services could see an uplift due to upcoming policies and programs.

- Several European banks, struggling to post healthy returns in the current low rate environment, trade below book value. The ECB has views initial signs of inflation and is revisiting its monetary policy. The shifting sands may have a medium-term upside impact on rates thereby helping banks’ profitability. M&A in the sector also remains potential particularly after Germany’s change of heart on deposit insurance.

- Cuts in Corporate Tax rates in the Netherlands and Greece should help the bottom lines of the overall business sectors in these countries

- The EU has little incentive to ease Brexit discussions for the UK. Despite its reliance on the UK for trade, the rise of the Eurosceptic extreme-right parties across the region, and particularly Salvini in Italy, pose an imminent threat to the Union. This summer, the EU will provide more clarity on its stance on the UK’s financial sector vis-à-vis EU regulations. A negative outcome could lead to a BoE rate cut.

Other Items to Watch in 2020

Aside from Brexit, here are some items we will be watching for the rest of the year.

- US Yield Curve Inversion: At the start of 2020, the US yield curve is flirting with inversion again stoking fears of a US recession. It spent 4 ½ months inverted last year and is known to precede recessions by an average of ~20 months. Some argue that the US Treasury’s current ~$2 trillion balance sheet distorts today’s yield curve making its predictive signal less reliable. Nonetheless, markets will interpret a prolonged inversion as a cautionary signal about the US economy and act accordingly. It remains a measure on which to focus in the coming months.

- Further Slowing of Global Trade: The US and China took positive steps towards finding a trade resolution this January by announcing Phase 1 of a trade deal. The deal sees the US reduce its 15% tariff on $120bn worth of Chinese goods in exchange for a promise from China to buy $200bn more of US manufactured goods, agriculture, and energy over the next two years. Other tariffs that were meant to take effect in December were also suspended. The deal brings some respite to the trade wars but significant tariffs on European goods remain and are likely to intensify over 2020 as both Digital and Carbon taxes from the EU loom. President Trump stated at Davos that he would like to agree on a trade deal with the EU by the November 2020 elections. More recently, the newly discovered Coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak and the ensuing damage to the global economy are being reassessed daily as organizations race to find a cure.

- CLOs: US leveraged loans registered a 7-year low default rate of 48% in 2019, comfortably lower than their historical default rate of 2.9%. The European leveraged loan default rate averaged 1.6% for 2019, also well below its long-term 3.5% average. Low defaults are partially due to the ample liquidity currently in the market buttressed by accommodative monetary policies. However, the well-documented decreasing loan quality and their continued take-up by a growing CLO market are causing some to worry. Approximately 80%, or $960bn, of outstanding leveraged loans is covenant-lite. And CLOs have grown substantially since the last crisis; US CLOs grew from a post-crisis trough of roughly $260bn in 2012 to $700bn today, representing more than half of the total $1.2 trillion leveraged loans in America. The CLO ownership causes worry because 75% of today’s leveraged loan issuances are purchased by CLOs and their disperse investor base includes SIFI institutions, insurance companies, SIB banks, and other financial entities.

- Italy: Italy has the potential to be more of a problem for the EU than Brexit given its integration within the Union and the shared currency. Despite rising factions of right-wing parties such as the AfD in Germany, National Rally in France or Vox in Spain, no far-right candidate has come as close to a premiership than ex-Deputy Prime Minister Matteo Salvini has in Italy. He remains popular with Italians and, judging by his past, would continue his confrontational approach with the EU if he does successfully ascend to the Prime Minister position.

- Separately, it is worth noting that the “Y2K-esque” ending of LIBOR at the end of 2021 is floating out there but could quickly become problematic for some investors. As a reminder, after bankers were found guilty of manipulating the rate in 2016, LIBOR’s administrator, the UK Financial Conduct Authority (“FCA”), announced that it would no longer support the mechanism and that market participants would need to seek alternative rates. The decision effectively throws more than $300 trillion in bonds, derivatives, securitizations, and deposits into disarray. Despite the looming deadline, progress on alternatives has been slow sparking concern with regulators. The FCA sent inquiries to several UK banks and insurers in late 2018 asking for details of their respective LIBOR transition programs. S&P announced it would begin factoring in LIBOR switchover preparedness in the future ratings of the financial institutions. We don’t believe that the FCA would completely sidestep LIBOR if significant market disruption would ensue. Which is why the regulator is agitating now, highlighting the lack of progress in a November speech. It is pushing for all interest rate swaps to be based on SONIA by Q1 2020 and for all new sterling loans to be based on an alternative rate from Q3 2020 onward. The changeover may have value leakage implications for investors holding LIBOR based loans or products with tenors past 2021.

Sincerely,

The Gorj Group

Anthony Ugorji, CEO